How the International Stabilization Force for Gaza Could, Over Time, Replace and Disarm Hamas

It’s incredibly complicated but we have to give it a shot.

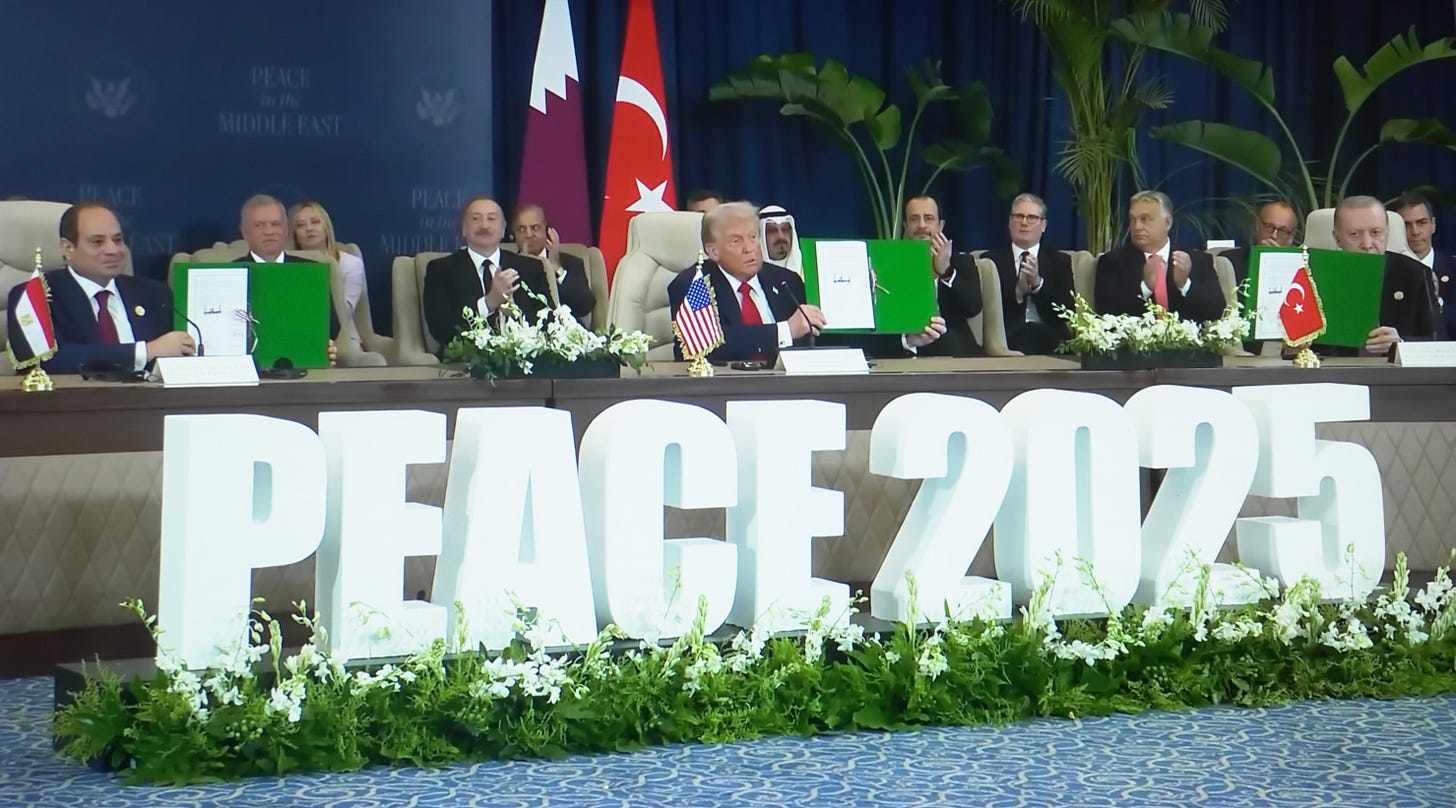

I spent the past weekend at the Doha forum – a massive conference with more than 5,000 participants from across the Middle East, the United States and around the globe. When it came to Gaza, one thing was clear: Everyone is waiting for the next move in the American 20-point peace plan. There are three central components to this plan: (1) The Board of Peace – the international mechanism for managing post-conflict reconstruction efforts for Gaza; (2) a Palestinian technocratic transitional entity to govern the Strip; and (3) the International Stabilization Force (ISF) that would ultimately create a security environment to replace Hamas.

By far the most complex and critical piece of this is the international force. Without it, there is no security on the ground, and without that, nothing else works. Yet there was little consistency, including from the Egyptian, Turkish, or Qatari foreign ministers, about what this force would actually look like, how it might come to fruition, what it would do, or how it fits into an eventual transition away from Hamas rule. And it wasn’t just the officials. I spoke to numerous experts who had different views on what this entity was meant to accomplish and how. The ambiguity is understandable. This is incredibly complex. But it is also disturbing. More than two months into a ceasefire and with an urgent need to transition to the next phase, there needs to be more public clarity on where this is all going.

When I was at the White House during the first year of the Gaza war, I spent a lot of time thinking about this force and the overall approach to post-conflict planning. I think there is a plausible theory of the case. Not a guaranteed path, but a realistic one. And it’s worth walking through it, step by step.

What is the theory of the case?

At its core, the theory is simple: you cannot transform Gaza politically unless you transform Gaza’s security reality. Basic counterinsurgency 101 says you need a legitimate, functioning alternative to the existing monopoly on force. Right now, that monopoly is Hamas. As long as Hamas remains the primary security provider – deciding disputes, enforcing order, intimidating opponents – no political shift will take root.

Ultimately, Palestinians themselves must provide security in a post-Hamas Gaza. Only a Palestinian force can credibly police Palestinian society. But such a force cannot appear magically. It needs time, space, training, and protection. And that’s the purpose of the international stabilization force: not to replace Palestinians but to create the conditions in which a genuine, grounded, Palestinian security structure that is not Hamas can emerge.

What would the force do?

The force would take on several tasks that we know – through painful experience – are essential in a transition like this. Think back to the “by, with, and through” model that was CENTCOM and the international coalition’s mantra for years as it fought ISIS: Partnering with local forces, helping them organize, providing logistical and intelligence support and creating breathing room for them to become credible actors.

In Gaza, the stabilization force should help train and enable new Palestinian police and security units; secure the routes for humanitarian aid; stabilize sensitive areas along the yellow line where incidents keep occurring; and offer a protective umbrella under which Palestinian institutions can regrow. The goal isn’t to run Gaza – it’s to shepherd the creation of an alternative to Hamas that Palestinians themselves will own.

Who would be in the force?

The ideal anchor is Egypt. No country understands Gaza better, and no country has more credibility with Hamas or more influence over what happens at the border. Turkey is the other major player with the military capacity and relationships to contribute meaningfully. Getting Israel to accept a Turkish role would be difficult, but perhaps not impossible – especially if Trump, who has a strong relationship with Erdoğan, leans on Netanyahu. With one or both of those as the anchors, you could also bring in others who have experience in peacekeeping, even if less of an understanding of the situation on the ground.

The US’s role is more ambiguous. Washington has signaled it will appoint a two-star general to help oversee the effort, but insists no US troops will enter Gaza. That’s awkward: It gives the US responsibility without control. Still, every participating country wants Americans involved in some way. For the Israelis, it gives the force greater credibility. For the Arab states – some of whom would participate – a US presence virtually guarantees Israel won’t mistakenly fire on the mission.

Where does the Palestinian force come from?

There is no ready-made “Palestinian national security force for Gaza” waiting in the wings. The Palestinian Security Forces (PASF) under the auspices of the PA is the closest option. But there is strong resistance from Netanyahu and his coalition partners to getting the PASF in, and Trump would have to be willing to spend a lot of political capital pushing Bibi on that, which he should. But even that is going to take a while, both because the PA doesn’t necessarily have the capacity yet and would have to have more forces trained to do this, and because it’s not clear that you could just bring in a bunch of guys from the West Bank to secure Gaza and have them have any legitimacy.

So the best option is probably to pull from multiple sources at once and see what begins to cohere. Some forces are already being trained in Egypt and Jordan under PA auspices. Some former PA security officers remain inside Gaza and could return to service. There are also “blue police” – basic municipal police officers who worked under Hamas but aren’t necessarily ideologically tied to it, and may shift allegiances once a credible alternative emerges.

The US has been through different versions of this problem many times in recent years. In Iraq, we flipped entire tribal structures away from their alliance with Al Qaeda during the Anbar Awakening in 2007 and 2008. In Syria, we built a patchwork of Kurdish and Arab tribal partners that ultimately helped defeat ISIS. We also had spectacular failures, like the $500 million effort to stand up a Syrian rebel force that collapsed in days (the folks that killed those guys are now running Syria, and we are working with them and just removed sanctions). The lesson is clear: You have to experiment, adapt, and work with what’s actually on the ground, not what you wish was there.

What about fighting Hamas?

This is where many people misunderstand the concept. The international force is not going in to fight Hamas. No country would sign up for that mission, and it would be a disaster if they tried. The force will not be waging firefights in the alleys of Gaza. Instead, the idea is to create a political and military environment in which there are understandings – Hamas does not attack the force, and the force refrains from attacking Hamas.

If Egypt and/or Turkey are central players in the force, Hamas will think twice before shooting at it. And those two countries, along with Qatar, have the relationships to essentially cut a deal with Hamas in advance to avoid shooting at each other. And as we have already seen, Hamas generally tends to fold when the entire world unites in a position against it (e.g. on the ceasefire agreement that ended the war). It is not hard to imagine a mutually understood set of red lines: the force is there to protect civilians and build an alternative, not to hunt Hamas, and Hamas agrees not to treat it as a military enemy and refrains from attacking it or the Palestinian forces being set up in Gaza.

What about disarmament?

Expecting Hamas to surrender all its weapons upfront – especially while the IDF is still in Gaza – is simply unrealistic. No insurgent group in history has done this, and insisting on it now ensures paralysis. Disarmament has to happen in stages. Early steps might involve giving up certain categories of weapons – especially rockets or heavy weaponry – or putting them into monitored storage.

The real progress will come as, over time, Palestinian security forces grow, political pressure builds and Hamas’ leverage shrinks. As Hamas loses power and leverage, it may be willing to accept more disarmament. And Hamas is far more likely to hand over weapons to a Palestinian-led force with Arab and international backing than to the IDF.

The strongest counterargument is that this would just recreate the Hezbollah model but in Gaza – where the Lebanese Armed Forces were in place, but Hezbollah remained the most important power broker. However, there is a better chance this play could work in Gaza than in Lebanon, because in Lebanon, Hezbollah had easy resupply routes with weapons being flown in from Iran to Damascus and then shipped to the Bekaa Valley. Gaza’s borders can be locked down in ways Lebanon’s never were, which means rearmament will be much harder, potentially shifting the power dynamic.

Why would Hamas accept this?

It’s a fair question, and the answer starts with reality: Hamas is in an extremely weak position. They’ve already accepted the idea of giving up governance to a technocratic committee. If Qatar, Egypt, Turkey and the rest of the region come to them with a unified plan backed by the global community, Hamas will face enormous pressure – and very limited alternatives.

Their internal calculation may look something like Hezbollah’s in Lebanon: allow a new governance structure to emerge, preserve some residual role, and hope to rebuild influence. Hamas will assume it can survive and have the “Hezbollah model” take root. The point of the stabilization force and the growing Palestinian security force would be to steadily prove otherwise.

So where does all of this leave us?

This will be messy. It may fail. It will certainly take time. But there are real reasons not to dismiss the idea out of hand. Gaza is geographically small. Its borders can be controlled. The international community, for once, is unusually aligned and mobilized. And the US actually knows how to do parts of this – not perfectly, but well enough to give it a fighting chance.

Would it have been better if this planning had started two years ago? Of course. Many of us pushed hard for exactly that. Netanyahu shut it down because it meant admitting that Palestinians would ultimately govern Gaza, and we are now playing catch-up on one of the most complicated state-building challenges imaginable. But we are where we are. The question now is whether we try something ambitious and difficult – or whether we resign ourselves to the status quo, where Hamas rules part of Gaza, Israel occupies another part, civilians suffer endlessly, and nothing ever improves.

This plan isn’t a panacea. It won’t erase Hamas overnight. But it might create space for a legitimate Palestinian alternative to grow and slowly marginalize Hamas. And while there is also a scenario where Gaza becomes Lebanon or Iraq with multiple entities, including Hamas exercising and competing for power, that would still be better than a Hamas monopoly of power in Gaza.

Ideally, this plan should be tied as much as practicable to the Palestinian Authority. And if it is conducted in parallel to an international effort in the West Bank that includes: Real reform of the Palestinian Authority; a shift by the Israeli government away from its 15-year strategy of undermining Palestinian moderates and empowering extremists (only possible after elections and a new Israeli government); and a mobilized international effort to fund and support the Palestinian Authority including through recognition of statehood, it could open the door to a unified Palestinian political project that includes both the West Bank and Gaza.

It’s a long shot. But the alternative of not trying at all and settling for the status quo – a permanently divided Gaza with a next round of fighting all but inevitable – is far worse.

We’re proud to be powered by supporters like you. Like many advocacy groups, J Street relies on End-of-Year donations for nearly half of our annual grassroots fundraising. Your support makes our important work possible.

Israel has engaged in Genocide since 1948. Our former President Franklin D. Roosevelt and General George Marshall opposed its creation, and they were correct and omniscient.

Innocent Jews in America and other countries are facing non-stop Anti-Semitism because of the Genocide carried out by Benjamin Netanyahu, the "Settlers" and rabid Zionists.

American Jews are Americans, just as I am.

See https://naegeleblog.wordpress.com/2023/10/31/americas-jews-are-americans/ ("America’s Jews Are Americans")